When you look at your life, you sometimes reflect on a defining moment that shaped it. I’ve had one experience that really ended up maybe not being the defining moment of my life, but something that set the stage of the person I was, would become, and the lawyer I became.

When I was in college at Stony Brook, I was heavily involved in student politics and the College Republicans. I was the President of the College Republicans and I really got disillusioned with politics so I opted to join the school paper, the Statesman. Since I have a great sense of timing, I became Managing Editor six weeks later. Despite never taking a journalism class, I won the top student journalist award my senior year. I pretty much won because as the grandson of Holocaust survivors, I beat back an attempt by some of my fellow editors to publish a Holocaust revisionist advertisement and wrote am article about it. I might have had a tiff with two people over that, but the majority of the editorial board rejected the ad.

When I went to the American University Washington College of Law in 1994, I immediately joined their magazine, The American Jurist. My first year there, I was just writing the humor column, because my goal like most law students was the opportunity to join Law Review and the other three law journals that the school had. Getting on to a law journal looked good on a resume.

To join Law Review, you either had to get on through grades or a write on competition. The write on competition would also include positions for the other journals including the Journal of International Law and Policy (known as ILJ). The editors of the ILJ were trying to put themselves on the same level as Law Review, so they intended to pick students based on grades as well. The spring short write on competition took place over the Easter Break for first year law students.

Friends of mine assured me I’d make it because 90% of those who participated in the competition the previous year got a position on a journal. Of course, what happened was that in my year, there was a 50% increase in the amount of applicants, so nearly 50% of the applicants including yours truly didn’t get a spot.

I was devastated; I thought the world was going to an end. Then I decided to get myself back up and remember that there was a fall writing competition called the long write-on in my second year and I could also use that submission for my upper division writing requirement. However, I heard rumblings about the write-on competition. The deadline for the short write-on competition was bypassed for some students with computer problems and then I heard rumors that despite the anonymity of the submissions to the competition, certain editors were tipped off on whom to select. The competition was supposed to be anonymous, you were supposed to put down the last four digits of your social security number on your submission, rather than the exam number given out by the Registrars office. What’s the problem? Well, our email addresses included the last 4 digits of our social security number, so how could they really be anonymous if it was easy to identify you through your email address?

The following fall, I tried out for the long write-on competition and failed again. I was resigned to being part of The Jurist and that was that. In a sense, I think it was a relief that I didn’t join one because it wasn’t really going to have any relationship to a career in tax law. So I wrote an article, blasting the entire journal system in The Jurist and happy that I wasn’t part of it. I also showed that the system of selecting journal members was flawed because it wasn’t anonymous. The administration didn’t pay attention.

For my final year of law school, I was the Executive Editor of The Jurist. I was very jaded about law school, so I made a point of articulating the problems and the hypocrisy of the place while offering concrete solutions for reform in my columns. The problem with the law school is that they tried to claim they were a non-competitive law school with an egalitarian spirit. They prided themselves that two women founded the school, but forget the fact that they wouldn’t admit African-American students at that time in 1896. So I was handed a story that would blow up that non-competitive vision.

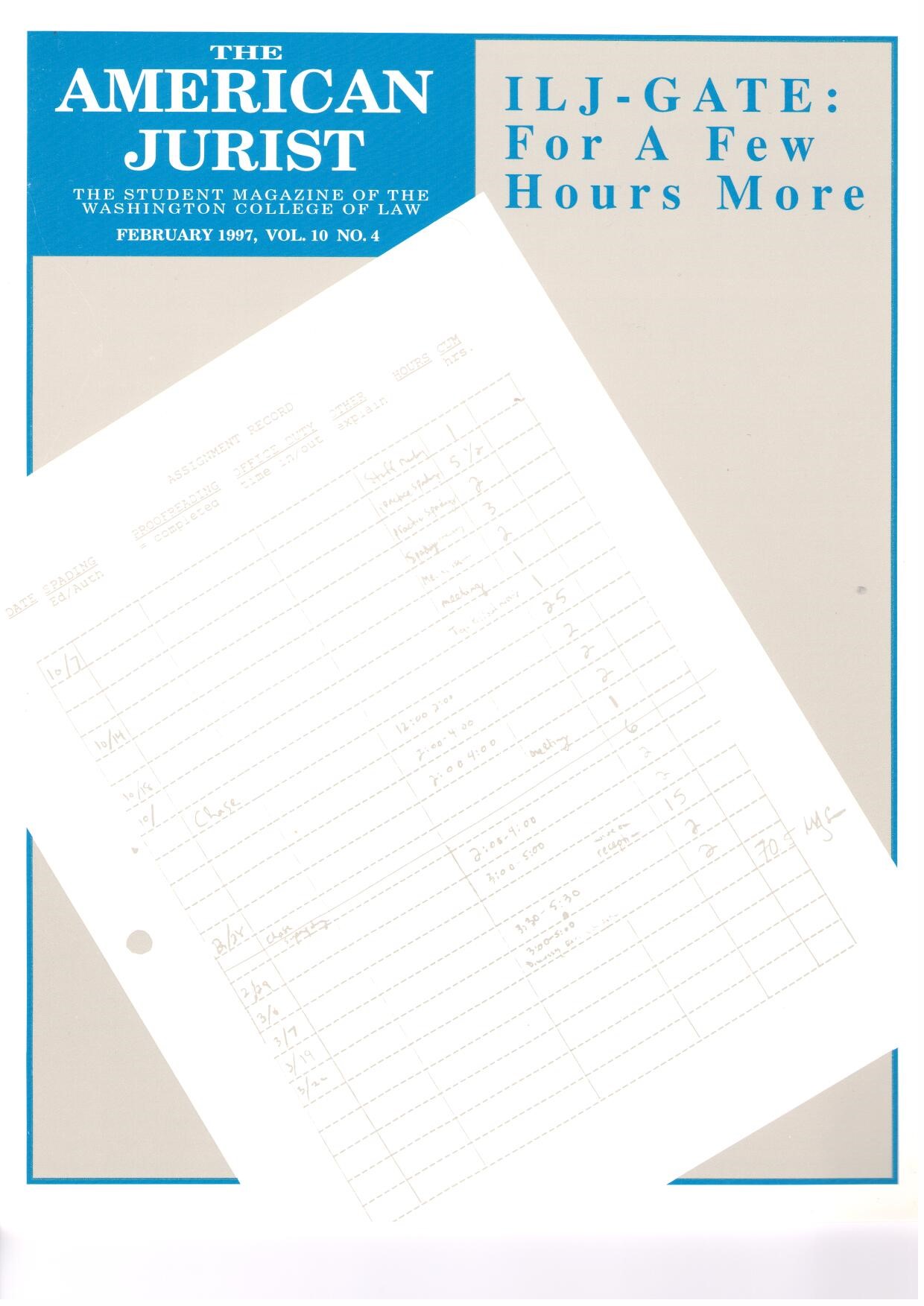

Two aggrieved members of the ILJ staff handed me copies of all the timesheets of the members of the staff for the previous year. While all members of the ILJ were supposed to complete 160 hours to get law school credit for the journal, it appeared that 51 out of 59 staff members didn’t complete the requisite hours including most of the staff that was elected to the editorial board. Of course, the two whistleblowers weren’t elected to the board and were angry that they weren’t selected for board positions. Unlike the Statesman where board positions were elected by staff members, the Board at the ILJ were selected by the previous editorial board. So favoritism might have played a part in board positions rather than merit.

Months before I ran with the story, I let the administration know. I told Jamie Raskin, a professor who used to be Associate Dean (and now a Congressman from Maryland). He instructed me to report this to Dean of Students with the information I had before the Winter Break. The Dean of Students did absolutely nothing. When I came back from winter break, I decided because many staff members would be afraid to write the story because of their staff positions on law journals, I would write the article along with my Managing Editor, who in his 4th year of the joint JD/MBA program was a former staff member of the ILJ having completed two years as a staff member.

I arranged a meeting with the editorial board of the ILJ and I recorded it. They were completely shocked that I had the timesheets. I anticipated a good response why those timesheets were incomplete; I got nothing. I thought that if they said they’d make a mistake in not finishing the timesheets, the story would have died and it didn’t because they changed their tact after our meeting. I offered them the opportunity to respond with their own article as a rebuttal, they refused after the next staff meeting. Their next staff meeting was a blistering attack on me that somehow I hated journals and wanted to destroy the journal system. I might have hated the whole journal system, but they could never get those timesheets to disappear. If I hated the journals, I’d try to find dirt on the other journals too but they all ran a clean ship. I wrote the story with the Managing Editor and it was a great article. I contacted the other law journals and was shown that their timesheets were complete and unlike the ILJ, they didn’t reward blocks of hours of credit for going to parties or contributing to programs like toys for tots. The other journals were transparent in the way they awarded credit.

The registrar admitted that it was up to the editorial board to verify credit awarded to journal members upon graduation. I didn’t know it at the time, but that was going to be a big deal.

The article opened up a hornet’s nest of issues that affected the law school. The big issue was the funding of the law journals and how the law school was profiting off of it. The funding of the law journals was through student government (the Student Bar Association (SBA)) funding and about half of the student government funding went to the journals. I thought that was inherently unfair because at Stony Brook because they were a public university, you couldn’t be denied membership to a club funded by the student government. Yet half of the SBA budget went to organizations I couldn’t be a member of because I didn’t make the grades or through writing. The law school was profiting off this arrangement because they awarded 6 credits a year for staff members and 8 credits for board members. They charged tuition for these credits and those are credits were they didn’t have to hire faculty form. The journals were a profit center for the law school.

The following issue, I blasted the ILJ for their lack of transparency and for their attacks. They had the opportunity to rebut the allegations, but they refused. The ILJ’s editor sent me a threatening letter from her lawyer claiming defamation, the only problem was that he was an international law attorney and her boss, so that went nowhere.

I was dismayed that the administration was doing nothing and I wanted to go to the Washington Post. My co-writer and managing editor was fighting with me on this and said if I went to the Post, then everyone was right about me in trying to hurt the law school. I acquiesced (which I regret to this day) and then the ILJ editorial board made an error. They clearly knew who the whistleblowers were and they were claiming that these two whistleblowers didn’t meet the hours requirement and neither did my managing editor. So they were going to single out the whistleblowers and my co-writer and singlehandedly deny them graduation while letting the other staff members skate by.

The Dean of Students was a nice man, but clearly incompetent. Someone in administration once told me that he either was incompetent or just tried to destroy things by purposely doing nothing. I took the Dean of Students aside and told him that if the alleged whistleblowers and my co-writer didn’t get cleared for graduation, I was going to the Washington Post. In a panic, the Dean of Students called a meeting with the law school Dean and the other Associate Deans. All the Dean of Students would talk about was my threat to go talk to the Washington Post while the other Deans devised a method to ensure all ILJ members would be granted graduation as long as they verified in writing that they completed their staff hours as required for the credit. The law school was going to bury the problem and then reform the system after graduation.

I was threatened by fellow law school students that blowing the whistle was going to dim my job prospects and there were angry ILJ members who were so misguided in their attacks on me because there was no story except that the cover-up was the story. The missing hours are still uncontroverted and unexplained after 20 years.

After graduation, the system was changed. The anonymous system of using your last digits of your social security number was eliminated. It was replaced by an anonymous number issued by the registrar. The Dean would have also ensure that the editorial boards would no longer have unfettered discretion in awarding school credit and the IJ renamed itself, the International Law Review to get away from the taint of this scandal.

I learned so many lessons from this including my determination to speak up and do the right thing. I protected fellow students from academic harm and I took the abuse for disclosing what needed to be disclosed. Doing the right thing is not only hard; it’s usually unpopular at the beginning. I also learned about crisis management and how this story was a complete non-story until the ILJ closed ranks and tried to make me the scapegoat for their stupidity in not filling out those timesheets especially when the other journals were diligent in doing their job. No one was complaining about the elections, hours, and awarding of credit for the ILJ and that’s what happens when you slam hard workers with derision and elect “friends” as editorial board members. The point for anyone is that if you have nothing to hide, show your cards.

When I was a lawyer 10 years later, history sort of repeated itself. I blew the whistle on something that could have been explained away. Instead again, there was a cover-up and attack on me. Unfortunately, there was no Dean to cover it up for this plan provider.

So if you wonder why I’m rather opinionated about what’s wrong with the retirement plan industry and my time at a certain law firm, it all goes back to the Spring of 1997 and my fight with the editorial board of the ILJ.